Welcome back to Glass Half Full, and thanks for reading! We’re continuing with the tale of a young scientist who realizes that life may already have been discovered on Mars. If you enjoyed the previous installment, why not share this one with a friend?

Sometimes a life-changing moment hits you in the face, like a brilliant job offer or a marriage proposal. Other times it sneaks right by you, unrecognized until long after. The latter was the case with the moment that led to Joan’s ouster from NASA. In hindsight, the seismic event happened the instant she opened a gray file box containing the records of an old Viking lander experiment.

That moment was months ago now. As a newly hired research assistant with NASA, fresh off a post-doc fellowship at Harvard, her first task was to comb through the agency’s archives, flagging documents to be culled. Since its consolidation with the defunct National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NASA needed room to house the joint archives. Once flagged, the old NASA records would be moved to deeper, less frequently accessed storage in Virginia.

She spent her days in the sterile archive room with its rows of gray shelves holding row upon row of gray vertical file boxes. The air was odorless and triple-filtered, the temperature chilly (she always brought a sweater or down vest), the humidity kept at a constant forty percent. The intermittent hum of the ventilation system provided the only sound, so she always brought earbuds.

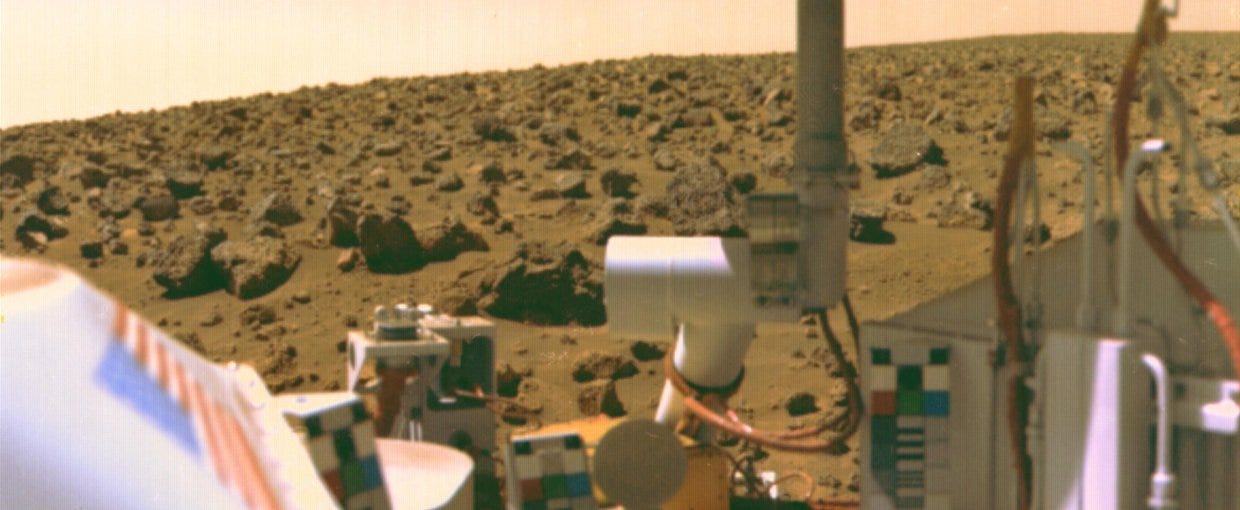

The gray box was exactly like all the others — nothing to mark it as extraordinary or life changing. It was cataloged as Viking I & II, Labeled Release Experiment, Gilbert R. Levin, PhD and Patricia Ann Straat, PhD. It contained a short summary of the experiment and its methods, and page after page of results in simple linear graphs. The latter drew Joan’s attention first. She leafed through the pages, each practically identical, the y-axis ascending rightward like every “line goes up” crypto meme from the ‘20s. The positive result couldn’t be clearer. Except that this positive result was for bacterial life on Mars.

The description of the experiment was simple. It was the same basic method used to detect bacteria in drinking water on Earth. Feed a sample a variety of foods bacteria like to eat, then wait for telltale indications of bacterial digestion, mainly bubbles of CO2. If none appear, the sample is sterile; if they do appear, the sample contains life. Since this experiment took place 225 million kilometers from Earth, the bacteria food had been “labeled” with a radioisotope. If that isotope rose into the detection chamber, then CO2 was present.

After the positive results came the control results. Once the initial test was complete, the samples were heated to 160 degrees C, a temperature high enough to kill most life. Then the test was repeated. If the result was still positive, then both results were likely false. But if it was negative, Levin and Straat reasoned, this would rule out a false positive for the initial test, supporting the evidence that life had been detected. All of these graphs showed a flat line — living bacteria were no longer present.

As a grad student in exobiology, Joan had of course heard of the Viking experiments. But the results were written off as inconclusive and contradictory, since two other Viking experiments to detect life-supporting conditions had come up negative. The positive results must be due to a chemical reaction, not a biological one (despite the results of the control tests).

Joan’s focus was on exoplanets, so perhaps she hadn’t paid enough attention to what had gone on during the early exploration of a local planet. One NASA statement about the Viking experiments read: “Despite signs that some nutrients were being consumed, most of the scientific community concluded this was likely due to non-biological reactions, dousing an initial spark of excitement over the possible discovery of life on Mars.”1 The subtext of her professors’ statements was always the same: you don’t want to end up like Gilbert Levin or, worse, Percival Lowell, the famed astronomer who was certain he saw canals on Mars through his telescope.

But now, looking at these graphs with their confidently upward-trending lines, she had to wonder. Why had NASA given up the search for extant life on Mars after Viking? The results were hardly conclusive one way or the other, as the scientists themselves stated in a documentary after the mission. If this wasn’t a case where more research was necessary, then nothing was.

The official answer was that scientists realized they had to study the context for life on Mars before looking for life itself, to avoid the kind of conflicting results the Viking mission had produced. That rang hollow to Joan’s ear. The science of life detection had only advanced in the last sixty years. Why not send a mission with an array of modern equipment? True, a few ideas in this direction had been raised, but nothing had ever come of them. Everything was riding on the upcoming Mars Sample Return mission, currently on its way back from the Red Planet. Due to funding cuts, the mission had gone ahead only with additional support from one of the country’s space billionaires, one with a particular interest in colonizing Mars.

Now Joan’s task was to decide what to do with this particular box. Keep it here in the main archives, or ship it off to the deeper storage site in Virginia? Her rubric for the choice was clear: age of the material; importance of the mission in the history of NASA; and importance of a particular document to that mission. So even the most peripheral correspondence related to Apollo 11 should be kept, while a good half of the Apollo 14 material could be shipped out.

The Labeled Release experiment seemed like a no-brainer. As the first mission to Mars, Viking was clearly important to NASA’s history. And as one of the three core experiments on the two landers, the LRE was vital to understanding the Viking mission. She put the file folders back in the box, closed it, and stuck a red tag to it. Red for Stop, green for Go Away. She got up and reshelved the box, not imagining how this one choice would affect the rest of her life.

Here’s Chapter 3.

Thanks for reading, and I hope you enjoyed it! If you did, please consider hitting that like button, sharing it with your friends, or even subscribing or upgrading your subscription. And please leave a comment with your thoughts!

Via science.nasa.gov (I don’t usually give an “accessed on” date, but who knows how long any of these government websites will exist? — March 28, 2025.)

As I read this, I find myself wanting to go research Mars missions to find where historical events turned fictional in your storyline. You do an amazing job of giving us readers enough facts (or presumably fact-based details) to make this scenario feel real. I imagine you researching and asking yourself, “yes, but what *if* they did X instead of Y.” Is that how it works in your brain?

Quick question:

Now that we know earth is flat, I am guessing Mars is also flat...?