Welcome back to Glass Half Full, and thanks for reading!

This is the third, and maybe final, part of this vignette about a young woman finding a place for her art amidst a sea of AI-generated “content.” (Here’s the first part if you missed it.) Not sure where it would go after this, if I chose to continue it. Maybe you can give me your thoughts in the comments! For now, enjoy.

Amy watched the auction on a monitor from the viewing room down the hall, surrounded by her fellow artists, writers, and other creatives. The mood in the room was supportive, mostly, each artist’s attention locking on the monitor when their own piece came up, the room growing quieter. Then congratulations or sympathetic noises, depending on the outcome. Only a few refused to watch, sitting in corners, staring at laptops or phones.

Now it was Amy’s turn. The screen showed the auctioneer and the stage he stood on, not the audience of bidders. “Next up, Lot 45, Item 4, ‘Spring Ice,’ by Amy Foster.”

Assistants wheeled in an easel bearing the work. “As you can see,” the auctioneer went on, “the work consists of several pieces. The buyer can display them any way they wish, though we recommend something similar to what we show here, for maximum authenticity. The central piece is the framed pen-and-ink drawing with accompanying calligraphed text. The other pieces attest to the authenticity of its purely human creation — pages from Ms. Foster’s notebook, Polaroids taken on the day, plus the looped video of Ms. Foster at work on the banks of the Huron River.”

That had been a good day — early March, five years ago now. The winter had been the coldest anyone could remember, a polar vortex descending from the Arctic for most of February. The Huron had frozen over for the first time in years, ice forming six or eight inches deep. Then the sudden thaw, the weather warming by forty degrees in a day. The next weekend, with the forecast for sixty with sunny skies, she and Chris couldn’t resist the urge to get out of the city. Not only for the opportunity to see something different, wilder, but Amy hoped to find a good subject for a drawing.

They drove out to a park along the Huron north of Ann Arbor, where they found a trail leading through forest and then along the river. Chris had insisted on bringing his GoPro and the old-fashioned instant camera. “You need both ends of the technological spectrum to document your work,” he said. He wasn’t wrong. Art buyers demanded ever greater evidence to prove a work was entirely human-made.

The snow at the park had mostly melted, leaving the trails muddy and slushy. The sun was bright, but a brisk wind made it chilly, especially in the scant shade provided by the bare trees. This always seemed the bleakest time of year, when Amy found it hard to believe the trees or grass would ever turn green again. The only color came from a single yellow feather lying at the side of the trail. Chris snapped a photo of it, also filming with the GoPro strapped to his head.

“Do you really have to use that thing?” Amy asked. “It makes me feel awkward.”

“Yep, we have to capture the whole experience, in case you come up with something great. Just forget I have it on.” That was hard to do, since the camera looked like a giant third eye in the center of Chris’s forehead.

Amy shivered in her sweatshirt. “Come on, let’s keep moving.” She envied Chris’s beard, which had to keep his face a bit warmer than hers.

The trail continued through more bare trees. Amy doubted they’d ever find anything inspiring.

Then they came to the river. It was a jumble of ice slabs, white with streaks of blue, piled one atop the other and refrozen in place. Logs jutted out of the ice at odd angles.

“Wow, I’ve never seen anything like that,” Chris said.

“Me neither,” said Amy. “My parents took me to a frozen river up north once, but I’ve never seen it broken up like that. We’re lucky to catch it at the right time. In a couple of days, it could all be gone.” She wasn’t usually so expressive. Now she felt like she was narrating a nature documentary for the camera.

They went on, coming to a stretch of open water with more slabs of ice floating down toward the jam. Amy paused. She liked the way one particular slab of ice angled up toward the sky.

They found their way down through a cut in the bank to get closer to the frozen stream. Here they were protected from the wind. The day grew warmer as Amy, sitting on a log, sketched the ice and the banks and the trees in her notebook. She took off her sweatshirt to feel the sun on her bare arms. Chris walked back and forth, snapping shots of the ice or of Amy with the Polaroid, still recording with the GoPro. Amy was so engrossed in her work, she hardly noticed.

The river burbled where the water dove under the ice, with an occasional louder thud of a new slab hitting the jam. In the trees, birds chirped and called. Amy didn’t know what any of them were, but they made the forest seem alive. She took a moment to stretch, feeling the sun on her face. It felt like spring was almost here, that soon the first flowers would burst open, the grass would turn green, and then the trees would put on their coats of leaves. She vowed to come back in summer, when it was truly warm, with the river shaded by the leafed-out maples and birches.

She knew better than to fall for the false hope of an early spring. The weather could easily turn cold and gray again, with freezing rain or slushy snow. But on a day like today, that was hard to keep in mind. She switched to pencil, and began scribbling words next to her sketch, mainly as a reminder to herself. She was vaguely aware that Chris had stopped moving around and was standing nearby.

Now the words she’d scrawled that day were at the center of this piece, calligraphed next to a refined illustration based on her sketch.

That feeling when

spring is almost here,

but not quite…

when the river breaks up,

but ice refreezes

in fractured chaos…

when the sap rises,

but the buds have

yet to burst…

when summer seems so near,

but winter could return

any day

The pen-and-ink drawing was black and white, save for a close-up of a yellow feather on the bank.

And there she was, in the video playing next to the framed art, scribbling away, birds singing in the background. And then Chris’s photos, of the yellow feather, the ice, and Amy.

She still wasn’t sure how she felt about the piece. It was an older one, and she didn’t have much confidence in it. Her skills as both artist and writer had grown since then, and she’d done well with her more recent works. Still, this was the first piece in her now signature format, with supporting documentation provided by Chris. She supposed it might have some interest for collectors. She paid Chris ten percent for his efforts. He deserved more since all of this had been his idea, but this was the largest cut he would take.

The auctioneer announced the amount for the opening bid. “Who will start us off?”

This was always the most nerve-wracking part. How long before the first hand went up? How high would the first bid be? Amy was pleased when the auctioneer acknowledged the first offer after just a second or two, and for two thousand over the starting bid. She smiled as the artists and writers around her gave a cheer.

She still found it hard to believe anyone would pay this much for her work. But the rich had developed a fetish for anything provably real and human-made. The masses listened to music created by machines, performed live by AI-generated holograms or in videos with lifelike avatars of whatever fictional singer or band. They went to movies generated by AI and played videogames generated by AI. Readers, what few were left, mostly turned to novel jukeboxes, where where they entered keywords for their favorite tropes, generating a new book in minutes. Humans just couldn’t compete, economically at least.

That didn’t keep them from trying. Writers continued to produce stories, poems, and songs. Musicians still played at coffeehouses, where the lack of a microphone proved the singing was real, not autotuned. People kept on telling stories, also in coffeehouses or bars, and through podcast or video sharing platforms, something like the old Moth Radio Hour, back when NPR had existed.

But the scale for all of this was so small that no one could make a living at it. It was just humans doing what humans had always done, back before anyone had an idea they could turn it into a lot of money. That had all depended on mass media, which in turn depended on a middle class. With just about everyone on Universal Basic Income now, that mass market just didn’t exist. Amy considered herself lucky to have found a niche and a market for her own work. She was one of the fortunate few who could live something like a lower-middle class life by catering to the tastes and needs of the rich.

It had changed her work, she had no doubt. She was less political now, for one thing. She’d never wanted all her work to have a political edge, but sometimes she found herself shying away from controversial topics. Nature themes were much safer. Sure, the moral panic of the ‘20s had mostly subsided and the algorithms were no longer so restrictive — as far as anyone knew. It was hard to tell, when all media and platforms were owned by three companies. Even the “independent media,” which had risen with the demise and oligarchic capture of legacy media, now all sang with the same voice. The ones who did say something different never managed to gain more than a few hundred followers.

Amy felt fortunate in this regard as well. In some ways, she had more freedom of expression than even the most obscure blogger. Sometimes she got rebellious and poked the bear with a more political piece, usually something to do with equal rights and the still-simmering culture wars, or else the plight of the people getting by on UBI alone. These had been some of her more successful works, and hadn’t caused a noticeable dip among her potential buyers. The rich loved to view themselves as open-minded and magnanimous, and supporting her more political works proved it. She had no doubt that a piece explicitly attacking the political and economic underpinnings of the new US technostate — assuming she could even fit that kind of message in her usual style of work — would cause her market to quickly dry up. And even after ten years of slogging away at her art and developing a market for it, the rent was always due at the end of the month.

“Going once…” the auctioneer called. “Going twice… Sold, to Bidder Number 7.” Amy was pleased with the final bid. The room cheered, and she nodded at her colleagues. That would pay the rent for the rest of the year and help Chris afford his hormones.

She headed for the restroom to get ready for the meet-and-greet, a conversation with the artist being one of the perks for the winning bidders. It was a chore, but not too onerous. The wealthy were always friendly to the beneficiaries of their patronage. And it wasn’t like she had no practice hobnobbing with the wealthy. At these moments, she always said a silent thank you to her Aunt Susan. All those galas had been worth it after all.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed today’s offering, please click that little heart button or share it with your friends.

Does this seem like the end to you? Where else could the story go from here? Though I always had this ending in mind, it feels like I’ve left Amy in a bit of a conflicted situation. Or maybe leaving her as a vassal, even a more comfortable one, of our fast-approaching technostate just isn’t very satisfying.

And speaking of that fast-approaching technological hellscape er, utopia er, uncertain future, OpenAI just announced a new artificial intelligence model that is “good at creative writing,” according to The Guardian. I have to say, the imagery in it seemed pretty sharp. And Jeanette Winterson says it’s “beautiful and moving.”

If all that leaves a bad taste in your mouth, wash it away with this old story told by

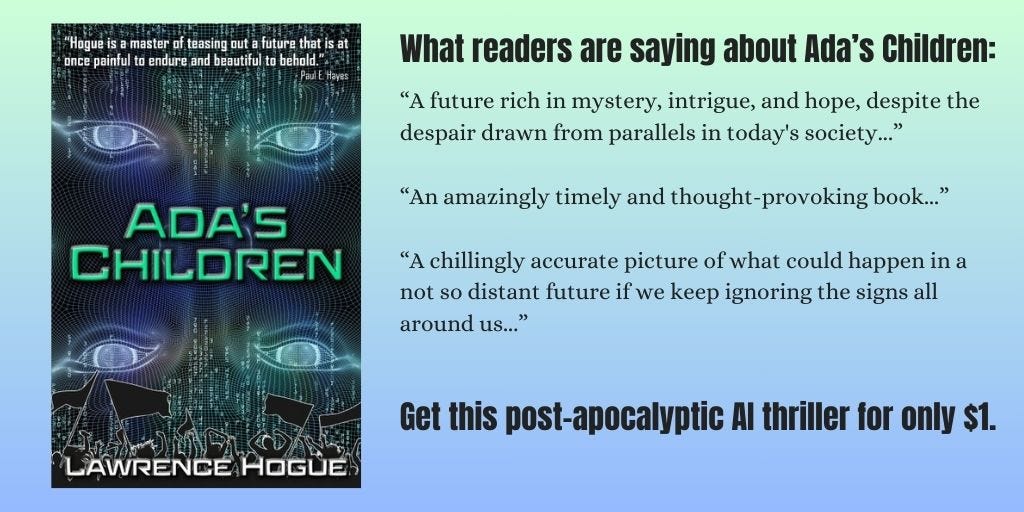

. I’m betting that’s all any of us will be doing, sometime in the not too distant future, telling stories around campfires. Better save up some good ones, along with the canned food and ammo.For a different take on the future of AI, check out my post-apocalyptic cli-fi novel at books2read.com.

This is clever.

Very nice -- I liked the gentle connection with the first part. This definitely feels like a world worth making a bigger story in, and fleshing out what it's like to live in it. What would it really be like to live in a world dominated by AI? (I say "would", not "will", because I'm holding out hope that it's just another fad.) We're so used to encountering great human art, in such an appallingly casual way. I mean, how much genius is just background music in a supermarket? If we never saw/heard/read any of that, and lived our whole lives that way, and then experienced something truly new and authentic, how would we react? Maybe we wouldn't even have the capacity to notice? It seems like such a rich environment to tell a story in.