Welcome back to Glass Half Full, and thanks for reading! Today’s offering is a vignette about AI moving into the areas of writing and teaching, and one possible response. As a bonus for Valentine’s Day, there’s a reference (and a link) to an old sci-fi love story by Kurt Vonnegut. This is Part 1, with two or maybe more parts to come, one each week.

Paul Jennings suppressed a groan when the message alert went off. Howard, it’s the phone! screeched a woman’s voice from the basket full of cell phones sitting by the door to his classroom. This was AP English, and his twenty-eight juniors were in the middle of an exercise, pens or pencils skritching across lined paper.

The skritching stopped as the racket went on. I know it’s the phone, Ma, I hear the phone! Paul scowled around the room. He stood in the center, having paused in his habitual pacing among the rows of desks as the kids worked.

“Who is it?” asked Eric, the wiseacre in this period, in a high, sing-song voice. “Whose mommy’s calling? Who forgot their lunch money?” A torrent of giggles washed across the room.

No one responded, but one student, Amy Foster, sat frozen in the front row, her shoulders hunched up nearly to her ears. Slowly her hand went up. “It’s mine,” she said so softly Paul could hardly hear. “That’s my emergency tone.” More giggling.

“Then you’d better get it,” Paul said.

He was surprised. Three months into the school year, Paul had Amy pegged as the good student who would never break the rules. But he didn’t know much about her family, just that they lived in Birch Highlands, the McMansion part of town. They should have known to call the office in an emergency, but maybe the aunt didn’t know that. Not all the teachers at Birchfield Academy enforced a cell phone rule, which complicated matters for those who did.

By now Amy had fished her phone from the depths of the basket. The tone ended. “Hello,” she almost whispered into it.

“Take it in the hall, please,” Paul said. Amy left the classroom with an apologetic look. “Back to work, the rest of you.”

“Fun time’s over boys and girls!” Eric called out from the back.

The students returned to their tasks without too much grumbling. It had been a long ten weeks, but by now they were used to the routine in crazy Mr. Jennings’ Luddite classroom. He was the only English teacher at the academy to require all his students to do work by hand, in class. He suspected it was the first time any of them had needed to do their own writing in years.

It had taken a lot of effort to get them to this point, weeks of lectures and exhortations. First, the one about not giving up on language, humanity’s one true birthright, ceding it to the AIs. What was it that made humans unique, if not their ability to transmit culture from one generation to the next through oral tradition? What made human civilization possible, if not the ability to transmit that culture beyond living memory in the form of symbols, whether carved in stone, inked on papyrus, or printed on a Gutenberg press? And now to give all that away because machines could imitate the human mind, creating a simulacrum of cognition by mindlessly manipulating those symbols?

And what about independent thought? By turning your writing over to an AI, you let the algorithm decide what you could say, or even think. All the platforms manipulated information in various ways. The Chinese DeepSeek, now banned in the US, wouldn’t let you write the truth about Tiananmen Square, while OpenAI and Google had shifted their answers on the January 6 Insurrection in disturbing ways, rebranding it as a rebellion of patriots against corrupt elites and a fraudulent election.

No, humans did not have to give in to the machines, nor should they. He’d tried to convince his students this was the cause of their generation. He printed out a slogan, Fight the Machines!, in banner type and hung it at the front of the class.

Surprisingly, some of the kids seemed to have bought it, though he was sure they still used AI in their other classes. Their favorite exercise had been early on: campfire tales in which students re-enacted humanity’s oldest language tradition, telling stories around a fire. Not a literal fire, but he’d decorated the classroom in a forest-and-savannah theme and brought in a portable electric heater with fake flames for the campfire. The students brought in whatever tales they knew, mostly ghost stories from Scouts. But a shocking number had nothing, having never heard a story told out loud in their lives. He hoped to get at least some of his students outside for an actual campout in May, if the weather cooperated.

As difficult as all this had been, it beat the hollow stares of his colleagues when he saw them in the break room or in department meetings. Unwilling to go to the lengths Paul had, none of them had found a way to keep their students from using AI, not just for research or assistance, but simply to write their papers for them. Paul suspected some of the other faculty used AI to grade the work, which reminded him of the name of a 1970s punk band his dad used to listen to.

Amy returned with a mouthed “Sorry.”

“Everything all right?”

She nodded as she passed him.

* * *

Amy walked back to her desk, her eyes on the floor. Was it hot in here? She was sure everyone was looking at her. Why had Aunt Susan called her in the middle of the day? Why had she overridden the do not disturb setting? It wasn’t an emergency, she’d just wanted to make sure Amy attended next week’s gala for the hospital.

Now Amy regretted telling her mother she didn’t want to go. That must have made its way back to her aunt, who was on the hospital board and headed the gala committee. Apparently, the presence of the chief of surgery’s entire family was so important it required a phone call interrupting class — which she didn’t care that much about, except for the embarrassment.

Not that she didn’t enjoy English, though she tried not to let anyone else know that. Same with all the books she read, always on her phone, so her friends would think she was just scrolling Insta, or Red Note before it was banned. She always made sure to have Insta open to some hunky celebrity’s account, to avoid suspicion.

The only times she read a physical book were when Mr. Jennings assigned one, usually a massive novel or collection of stories, or when she got together with her best friend, Tina. They had a two-person reading group, and they’d meet in a distant park or library so as not to be seen by any of their other friends. If you did that kind of thing in New York City, you were one of the cool kids and even got media coverage. But here in this medium-sized Midwest town, you were just the nerdiest of the nerds, and not in a good way.

So AP English was a breeze. Read some poems or stories and give your thoughts about them — what was so hard about that? Why would anyone ask an AI to write that for them? But a lot of students must be doing it, or Mr. Jennings wouldn’t go on his rants about it, or make them turn in all their assignments in handwriting — manuscript form, as the teacher called it — manu–script — hand–writing.

Amy realized she had an advantage, having grown up in a bookish household. Her mother, a literature prof at the local university, had read stories to her from the time she could hold her head up. Hearing or reading stories and then talking about them was second nature to her.

No, if you were going to use AI, much better to have it do something useful, like solving the quadratic equations in the hated math class her father insisted she take.

She was done with her assignment now, a response to a Kurt Vonnegut story about a computer writing love poems on behalf of one its programmers, and then falling in love with the love interest. The story made her feel pretty creepy, since the programmer had tricked both the computer, which committed suicide by short-circuiting, and his love interest, who ended up marrying him.

She started doodling in the margins — her other favorite class was art, so she put some effort into it, using a set of colored pencils. She drew the vast computer with its tubes and spools of tape, yards of printout spewing from it — the story was from the 1950s. Nearby, she drew the lovelorn programmer, sitting in his chair with a dazed look, cartoon hearts over his head. Or maybe she should give him more of an evil vibe?

Mr. Jennings was still roaming the classroom and stopped behind her desk. “Done with your assignment, Amy?”

Two embarrassing moments in one period! She shrank further into her seat, barely managing an “Mmhmmm.”

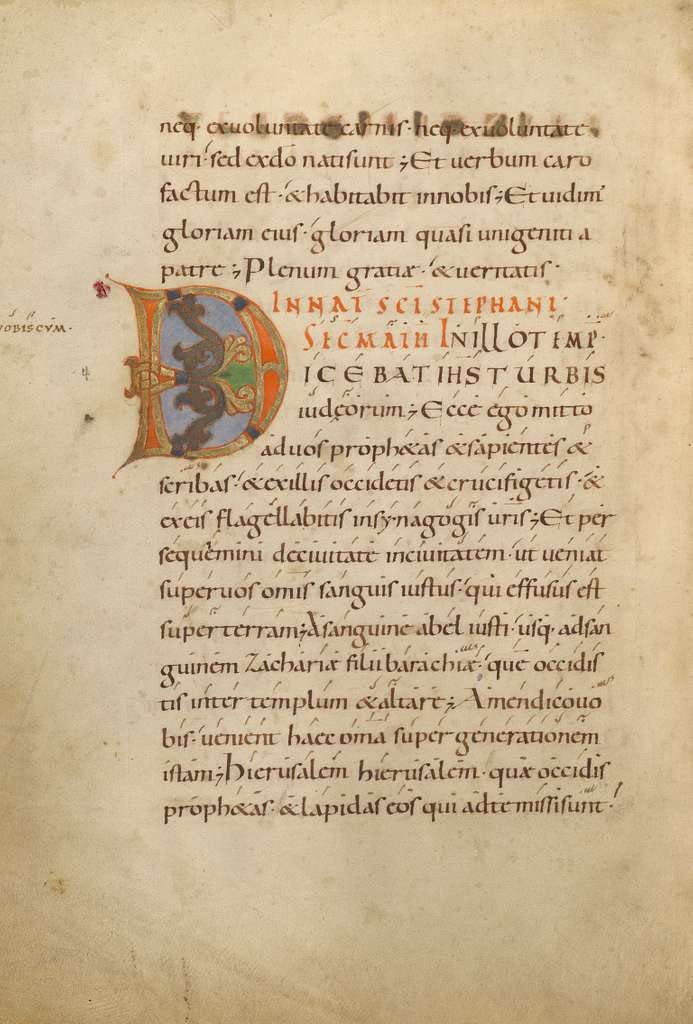

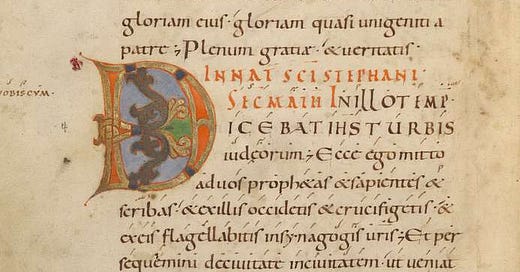

Mr. Jennings took up her notebook and examined the drawings. “These are nice! Connected to the story too, I see.” He held the notebook up for the rest of the class. “New rule, students — extra credit for illustrations accompanying your assignments. And what did they call an illustrated text in the days before the printing press?”

“A comic book?” Eric said to general laughter.

“No, Mr. Larsen. They called it an illuminated manuscript, the drawings helping to transmit the light of knowledge.”

Amy was mortified, or dead, as her friends would say.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed today’s offering, please click that little heart button or share it with your friends.

Where do you think this vignette will go from here? To find out, click through to Part II.

Have you read Kurt Vonnegut’s short story, “EPICAC”? Can it be considered the first sci-fi story centering on AI?

What band do you think Paul was reminded of when thinking about teachers using AI to grade papers written by AI? (Hint: it was a 1980s LA punk band.)

Paul Jennings reminds me of some of my favorite teachers of all time, and campfire tales would have been more helpful than 99% of my graduate school classes!

Excited for this new storyline from you!